Each year, doctors diagnose about 1,000 Americans with cystic fibrosis, a rare hereditary disease that affects about 30,000 people in the United States. Thanks to advances in treatment, people with cystic fibrosis often live until their early 40s, but there is no cure for the disease.1

Life-threatening rare diseases like cystic fibrosis affect about one out of 15 people, or 400 million, worldwide according to International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA). Many of these rare diseases have therapies available to curb symptoms, but no effective treatments.2

Pharmaceutical manufacturers and biotechnology companies are working hard to address these unmet medical needs. However, difficulty understanding underlying disease mechanisms, as well as the challenge of finding adequate sample sizes, have made the process of bringing orphan drugs to market a frustrating process.

Patient registries assist orphan drug development by giving manufacturers access to clinical, genetic, and biological data from a large patient population. Using registries, sponsors can better understand the disease, its history, and patients’ needs, all of which benefit clinical trial design and effectiveness.

Rare Disease Challenges

Because a rare disease, by United States definition, affects 200,000 people or less, researchers face more than a few hurdles when studying that disease. There may not be much, if any, data on disease prevalence, which makes it hard to determine study size. Little information on symptoms or treatment practices makes it difficult to develop data sets. And because many rare diseases affect children, ethical considerations and more complicated logistics come into play.

Patient Registries and the Problems They Solve

A tool used in the healthcare industry for decades, patient registries are being used in clinical research with increasing frequency, especially in rare disease research. Registries help stakeholders better understand disease burden, disease progression, disease genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity, and potential endpoints (or surrogate endpoints) that may be used in therapeutic clinical development.3

As pharmaceutical companies move toward patient-centric clinical trial development, patient registries help them understand quality of life issues, financial burden, and other issues that one can’t find in electronic medical records (EMR). Because patients worldwide can participate, sponsors can potentially acquire the sample sizes needed to develop successful studies.

Other benefits of rare disease registries include:

- During the pre-approval phase, researchers can use registry data to learn more about the disease and disease subtypes, identify and communicate with potential study participants, and identify physicians with extensive experience treating patients with a rare disease.

- Post approval, sponsors can use registries to determine how a treatment performs in the “real world:” they can assess how the treatment works in certain subpopulations, monitor patient safety, and market the drug using data from registries.

In the case of Elaprase, a drug used to treat Hunter syndrome, regulators wanted follow-up information to investigate the drug’s long-term effects. Because the clinical trial was limited to patients age 6 to 31, researchers had no efficacy information for younger patients. Using a disease registry, they were able to analyze safety and preliminary outcomes in this younger age group, resulting in premarket approval of the drug for children under age six.4

- Patients who participate in registries can receive information about their disease, chart their progress in treatment, and become part of a community of individuals who share their struggle.

- Regulatory agencies recognize the value of rare disease registries. The FDA considers rare disease registries, “…as a complement to randomized clinical trials to ‘fill in the blanks’ about outcomes that were not addressed in the limited controlled studies.”5

Categories to Include in a Rare Disease Registry

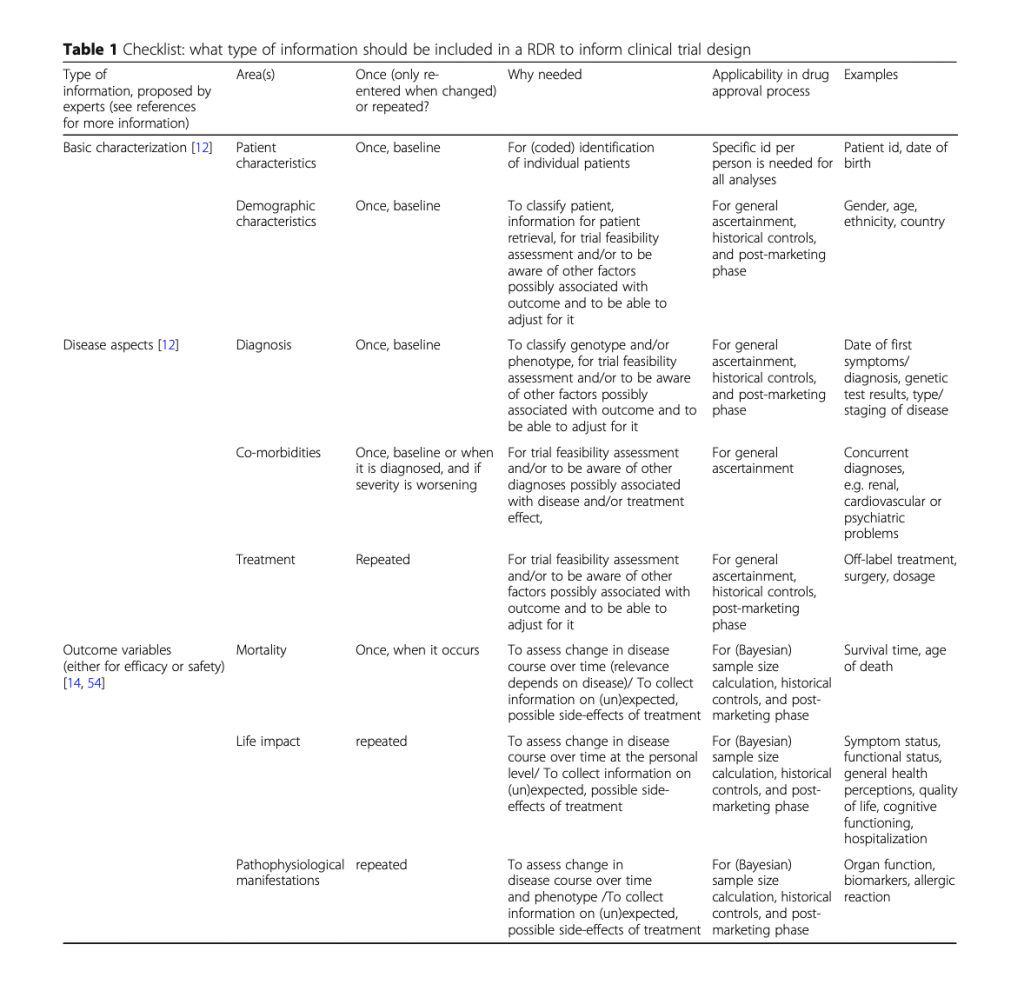

A study published in Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases provides a checklist of data elements to include in a rare disease registry. Elements range from basic patient information to quality of life and biomarkers. Rather than reinvent the wheel, we provide it here:

The Power of Patient Advocacy Registries

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation developed the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry (CFFPR) in 1966. It contains data for more than 46,000 individuals. While its main purpose is to better understand the disease, CFF also produces individual patient reports for providers and population-based reports for researchers.

In 2013, researchers out of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, used CFFPR to determine the efficacy of inhaled tobramycin on chronic lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients in a real world setting. Researchers concluded that using center-specific prescription rates from the registry was a “feasible approach” to determine treatment effectiveness.

As real-world data gains more widespread use, large patient registries maintained by advocacy groups and collaborations are becoming an important tool for rare disease research. A few notable organizations include:

- Patient Registries Initiative (PARENT), EMA’s initiative to strengthen contribution of patient registries for evaluation of medicines.

- Patient Registry Item Specifications and Metadata for Rare Diseases (PRISM), an NIH-funded project of patient registry questions.

- Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative comprised of 21 disease research groups and a data management and coordinating center. RDCRN studies more than 190 rare diseases. Access to individual-level data including phenotypic data tables and genotypes data from RDCRN studies is available through the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) by controlled access.

- A list of disease-specific registries can be found on the National Institutes of Health website.

Sponsors may also find that by developing patient registries, they eliminate some of the recruitment and enrollment challenges that come from developing treatments for rare diseases. Many of our sponsors build virtual registries to find and nurture rare disease populations. Sponsors use questionnaires and online focus groups to get feedback; in turn, they educate about the disease and treatment.

As drug development becomes more targeted, and more companies focus on rare disease research, patient registries will help fill in the blanks left by EMRs and other data capture systems.

Need help developing a patient registry or patient focus group? Speak with one of our program development experts.

For further reading:

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Landscape Review on Rare Disease Research Registries

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide: 3rd Edition (2014)

Resources:

1. McIntosh, James. “Everything you need to know about cystic fibrosis.” Medical News Today, January 11, 2018.

2. Rare Diseases (subtopic). International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations website, https://www.ifpma.org/subtopics/rare-diseases/.

3, 5. Gliklich R, Dreyer N, Leavy M, eds. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. Third edition. Two volumes. (Prepared by the Outcome DEcIDE Center [Outcome Sciences, Inc., a Quintiles company] under Contract No. 290 2005 00351 TO7.) AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-EHC111. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2014. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ registries-guide-3.cfm.

4. Jansen-van der Weide, Marijke C., et al. “Rare disease registries: potential applications towards impact on development of new drug treatments.” Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 2018, Volume 13, Number 1, Page 1. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.