Inclusion of women in clinical research has a surprisingly colorful history. As you can probably imagine, inequality is present throughout, but for reasons that may not be so intuitive.

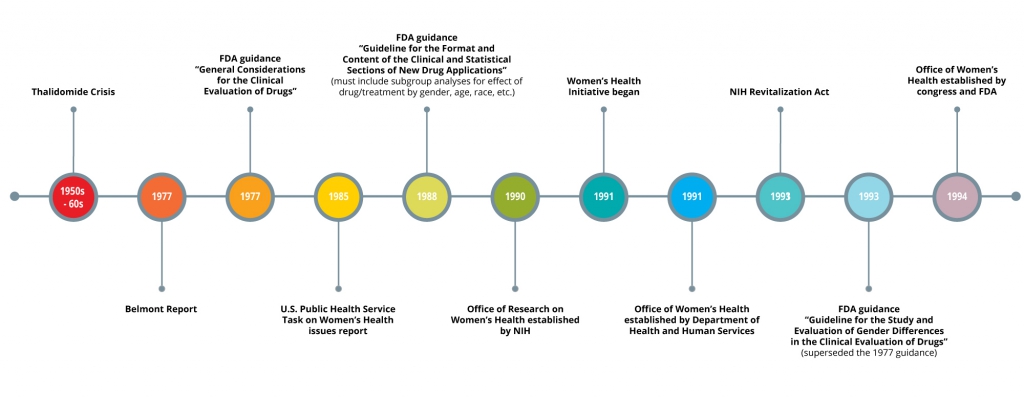

If you haven’t heard of the thalidomide crisis, here is a brief synopsis. In 1957, thalidomide was put on the market in Germany and a few other countries to treat morning sickness and other ailments. Then, throughout the next few years, thousands of babies suffered from severe birth deformities or early death. The birth deformities were attributed to thalidomide, and the drug was removed from the market in most places. Many countries took this crisis very seriously and subsequently reviewed and revised their regulations surrounding pharmaceuticals and clinical trials. Something most people may not know is that in 1977, the FDA released a recommendation called “General Considerations for the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs” that more or less prevented women of “childbearing potential” from participating in phase I and II clinical trials because of the “risk of pregnancy” and subsequent risk of harm to a fetus.

While this action was intended to safeguard human subjects, the result was that women were largely excluded from clinical research for the next few decades. In grad school, we were taught that women have been left out of research because menstrual hormones contribute to the variability of health outcomes, which is also true to an extent. Attitudes towards the inclusion of women may have also been subject to underlying social discrimination. Whatever the reason, the bottom line is that women can’t and should not be left out of research. It’s as simple as this: if research findings are to be extrapolated to females, they must be actually measured in females. Females have different pharmacokinetics, dosage requirements, and even adverse events, and male data cannot be used to predict this important female data.

And then the pendulum swung. In 1988 and in the years thereafter, many different initiatives began to advocate for the inclusion of women in clinical research. The NIH established the Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the Department of Health and Human Services followed suit with their own Office of Women’s Health. Bernadine Healy was appointed director of the NIH and immediately launched the Women’s Health Initiative, which resulted in several huge epidemiological studies of women’s health outcomes. Legislation changed the course of research guidance, mandating that the FDA establish an Office of Women’s Health and related guidance for industry. Attitudes have also begun to change; peer-review journals and federal funding agencies began to require justification if studies did not include both males and females. These were all important movements, on principle.

But have these initiatives changed anything? A very detailed history of analyses covering women’s inclusion in clinical trials has been published. Surprisingly, women seemed to be well represented in the 90’s and early 2000’s for the most part, but a more recent study of trials conducted between 1994 and 2009 showed that females accounted for only 37% of participants and that 64% of trials did not report on differences of treatment by sex, which was made part of the FDA guidance in 1988. What’s worse is that out of the 56 studies, only 3 acknowledged the limited generalizability due to lack of diversity in the study population, based on both sex/gender and race. It’s also been said that therapeutic areas that pertain only to women, such as cervical cancer or endometriosis, can be undervalued and underfunded.

Many reasons have been proposed to explain the continued disparity but there is no concrete answer. Recruitment strategies may not be thoughtful enough, and a general awareness of research may be lacking in women. If females are caregivers of young children, they may not be able to take time away from home to go to study visits. A great suggestion was offered to collect feedback from women at the end of trials to guide future recruitment efforts.

Researchers: remember to power your sample sizes to be able to detect any sex differences in trial outcomes. Sex differences in safety and efficacy are considered so important that the FDA’s Office of Women’s Health continues to guide research efforts to better detect them. Also, be sure to report measures of variability for both sexes so that future trials may be better informed, since variability of an outcome can be higher in one sex than in another – and by the way, it’s not always higher in females. Finally, if there are plans to submit clinical trial data to the FDA, guidance for NDAs reiterates that the FDA requires information based on subgroup analyses, which need to include sex and/or gender. While it may increase the budget to include more participants to account for these factors, remember too that likely half of your customers will be women.